Bergen-Belsen 80 Years On: A Liberation Marked by Suffering and Sobering Lessons

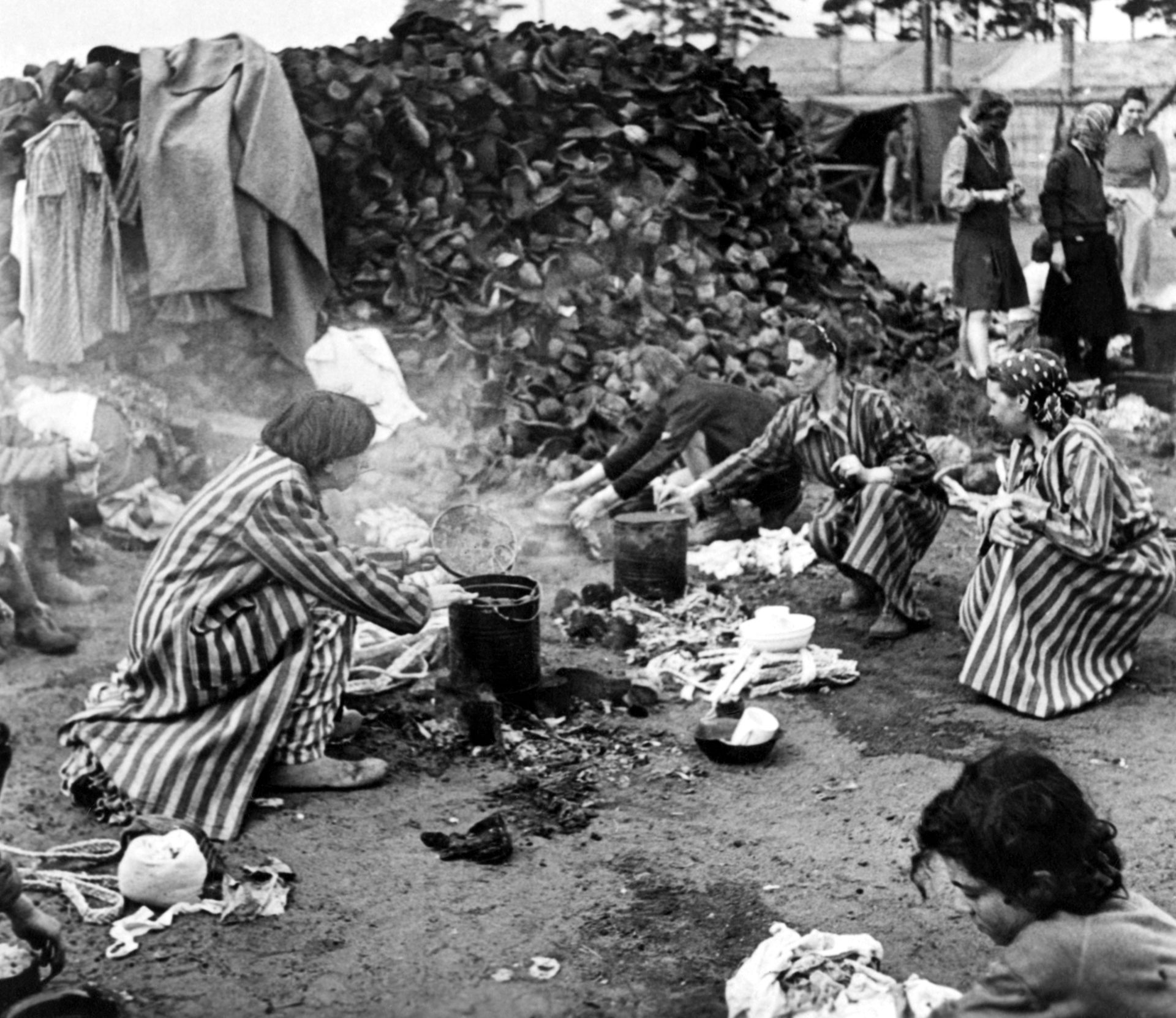

It’s hard to comprehend what British soldiers walked into on April 15, 1945, when they arrived at Bergen-Belsen. Eighty years later, the images still haunt — the skeletal bodies, piles of unburied corpses, the overwhelming stench of death and disease. And amid that chaos, another, quieter tragedy unfolded: the complete lack of protective clothing that cost even more lives, long after the gates of the camp were thrown open.

What many people don’t realize is that by the time liberation came, typhus had already begun decimating the surviving population. This highly contagious, louse-borne disease thrived in the filthy, overcrowded huts where inmates were crammed together without clean water, food, or sanitation. Clothes were a danger in themselves. Some desperate prisoners took garments from corpses just to stay warm, unknowingly exposing themselves to deadly lice. Others, terrified of infection, stripped down entirely. Anne Frank — a name etched into our collective memory — died here in such a state, just weeks before freedom arrived.

Also Read:- Blue Origin’s Glamorous Space Flight: Feminism, Fame, and the Final Frontier

- Bill Hader's Titanic Spoiler That Got Him Fired (and Made Him a Legend)

British soldiers, nurses, and medical students who stepped in to help faced horrifying conditions. Supplies were nearly nonexistent. Makeshift hospitals used newspaper instead of proper medical sheets, and dog bowls stood in for bedpans. Protective clothing? Practically unheard of. Many medics wore patched-together gear — a hodgepodge of British uniforms and scavenged German ones — and were doused in DDT, a pesticide later proven to be carcinogenic. Only the better-equipped Royal Army Medical Corps had full “typhus suits,” though they lacked face masks. Survivors were so traumatized, even the sight of those hazmat-like outfits caused fear.

In a chilling twist, German SS prisoners were forced to carry out the most dangerous tasks — handling infected corpses with bare hands and no masks. This wasn’t just a necessity; it was seen as retribution. Twenty of them died of typhus before they could even stand trial. In the absence of gear, vengeance and survival blended into one grim operation.

Then there’s the voice of Mala Tribich, a survivor who, at 14, was taken to Bergen-Belsen. She still remembers the skeletal figures, the corpses, the unbearable stench. She recalls being so sick with typhus that the day of liberation is a blur. And yet she lived. Now in her 90s, she spends her days speaking in schools across the UK, reminding new generations of what happened, and why it must never happen again. “We must guard against it,” she says. And she’s right.

Belsen’s story isn’t just about death. It’s about failure — the failure to protect, the failure to prepare. But it’s also about resilience, memory, and responsibility. Even now, as antisemitism resurfaces and world events grow darker, survivors like Mala are still teaching us. And it’s up to us to listen.

Read More:

0 Comments